The Cowee Tunnel is located in Jackson County near Dillsboro, North Carolina. Riders on the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad can see the remains of a train wreck left during the 1993 filming of the movie, The Fugitive, about a mile from the tunnel. Some scenes for the film were shot in Bryson City and Sylva, North Carolina.

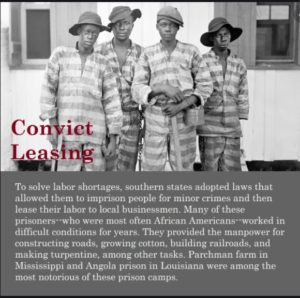

In the late 1800s, the far western mountain people were cut off from the opportunities of prosperity that were available in the eastern part of the state. The railroad brought increasing commerce to the mountain people in what was mostly wilderness at the time. If the Cowee mountain tunnel on the Western North Carolina Railroad Company line had not been dug, Dillsboro would have been the end of the hope for more reliable transportation for people and commodities west of Jackson, Macon, and Swain counties. When the new rail line construction reached Dillsboro, 500 Black convicts on the so-called “chain gang” from the state prison system of North Carolina were leased to the railroad to excavate, by hand-drilling, the ridge of solid rock the company ran into there.

In the late 1800s, the far western mountain people were cut off from the opportunities of prosperity that were available in the eastern part of the state. The railroad brought increasing commerce to the mountain people in what was mostly wilderness at the time. If the Cowee mountain tunnel on the Western North Carolina Railroad Company line had not been dug, Dillsboro would have been the end of the hope for more reliable transportation for people and commodities west of Jackson, Macon, and Swain counties. When the new rail line construction reached Dillsboro, 500 Black convicts on the so-called “chain gang” from the state prison system of North Carolina were leased to the railroad to excavate, by hand-drilling, the ridge of solid rock the company ran into there.

The Cowee Tunnel has a painful history, when it comes to the way the Southern Railway used the free labor of Black convicts, mostly young men. They worked under the gun and were treated in detestable and some say, evil ways. These men were forced to dig through the Cowee mountain by hand. The cruelty from White overseers and deaths of Black men who are buried in unmarked graves all along the rail line of the Murphy Branch of the Western North Carolina Railroad is infamous.

The convicts and armed guards were set up in a camp across the Tuckasegee River near the tunnel. For eighteen months, the prisoners had been shackled and chained together in groups of twenty and loaded onto a ramshackle ferry to cross the river to get to the tunnel job. It was maneuvered by the men who pulled themselves across while holding onto a steel cable attached to a hemlock tree on the other side.

On Saturday, December 30, 1882, a heartbreaking catastrophe happened. Fleet Foster, a White guard who was also on the ferry that fateful day, was the supervisor of the so-called “most dangerous” prisoners, many of whom had been imprisoned for loitering. One was only 15 years old. Foster kept them shackled in chains around the clock. That morning when they were halfway across the river, swelled by a storm the night before, the rear of the rickety flat-bottomed barge went under water. Twenty terrified detainees rushed toward the front of the barge, causing it to overturn.

Foster and his crew of 19 chained men and Anderson Drake were thrown into the cold, gushing current of the Tuckasegee River. The heavy chains and rushing undercurrent pulled the prisoners down under the river waters where they suffered a horrible death. Foster was saved by Anderson Drake, a young Black convict who was said to have been a giant. Young Drake, who was serving a thirty-year term, was the only convict saved. Fortunately, he was so large, the shackles would not fit him, so he was not chained to the other men. He risked his own life to save Foster who was drowning in the icy water. Reasonable people say he should have been exonerated for saving Foster’s life; but he was inexplicably found to have Foster’s wallet, with $30 inside, hidden in his prison clothing sack that evening. Even though Drake had risked his own life to save him, Foster had Drake brutally beaten with a rawhide whip by a foreman for the alleged theft and sent him back to breaking rock in the tunnel. Drake was even given more years in prison for the purported charge.

In the meantime, it took days for divers to find the bodies of the nineteen Black men who drowned in the Tuckasegee River that day. When they were finally found, they were hastily buried in unmarked graves on a hillside near the mouth of the Cowee Tunnel. The Jackson county storyteller/historian, Gary Carden says, they were buried in a trench with no marker and their relatives never found out what happened to their loved ones. People speculate that Drake, for the heartless treatment and lack of empathy by Foster, the very guard whose life he had saved by his heroic act, and the foreman who beat him, put a curse on the tunnel and on both men.

The foreman who had flayed Drake lost his job soon after that and was killed a few years later. The guard, William J. “Fleet” Foster, became severely disabled. In the early 1900s, the railroad lost a lot of equipment in the Cowee Tunnel and the Tuckasegee River because of runaway trains on Balsam Mountain, derailments, and cave-ins inside the tunnel.

Truth or fiction, local African American oral historian, Purel Miller said he has always heard that “the tunnel cries year ‘round with tears for the countless Black men who lost their lives over the many years it took to bring rail transportation to Murphy, North Carolina.”

The springs above leak onto the train when the train passes through the tunnel. Purel says, “It’s hainted. You can hear the sound of the pickaxes of the convicts hittin’ against the rocks and the men cryin’ from being whooped with rawhide whoops [whips] and dyin’ when they was drownin’ that awful day.”

Updated information about this tragedy is available from Gary Carden (gcarden498@aol.com) and Dave Waldrop (dewaldrop@frontier.com) of the defunct Liar’s Bench organization. See also Gary’s blog at hollernotes.blogspot.com.

Purel Miller lived and worked in Andrews, North Carolina and the surrounding area. He was known for his excellent recall of historical facts and people who lived in far western North Carolina. The Andrews Public Library holds a collection of books accumulated in his memory.

Some sources: The Sylva Herald; The History of Jackson County; Smoky Mountain News, Roaming the Mountains by John Parris, and archives of the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad.